27 Nov First-Hand From The Field: Why Expanding Our Reach Is Our Top Priority

On this beautiful day in November, we leave for the far north of Ifanadiana District. We are ready to leave for a week to see the progress of the rehabilitation underway at 4 of the most remote health centers in the district: Analampasina, Fasintsara, Maroharatra, and Ampasinambo. It would take us at least 2 travel days each to reach 3 of them individually. That’s why expeditions like this – most often carried out by members of our community or infrastructure teams – typically combine visits to multiple health centers at once, to optimize time.

On the road to Fasintsara, we come across men, women and even children carrying goods on their shoulders – basic necessities such as rice and oil – taking them to their villages in the commune of Fasintsara. Under a blazing sun, they walk for hours with their big bags. We are told that there are no other means of transport available at this location. This is also the mode of transport used to move medicines and other essential materials to and from the health centers on this axis of the district, including the construction materials we use for their renovation. So, currently, the people who live in this place have to walk at least 60 kilometers to find most of the food they need. Of course, if they have to go to other towns closer to the main road, it takes even longer.

Arriving in Fasintsara, we meet Dieu Donné (above, left), the Chief of Fasintsara Health Center, who shows us around the facility, which is already undergoing infrastructural renovation with PIVOT’s support (above, right).

He explains to us the challenges he and his team have faced every day for the five years he has worked there. In this remote corner of the district, one of the main problems is a lack of staff. There are only 2 health workers to provide care for patients at this health center: one nurse and one midwife. Recently, through collaboration with the USAID ACCESS program, they were able to have the support of a third person, a clinical aid. With the rehabilitation underway, Dieu Donné says he is happy with the new space made available to them for accommodating patients, especially given that, soon, PIVOT will start the implementation of the pilot project for universal health coverage (UHC) at this health center. This will include strengthening the pharmacy and covering costs for all patients, so the Chief anticipates an increase in the number of patients by at least double, hence the urgency of having a complete and qualified staff as well as adequate space to receive them.

Welcoming malnourished children remains a challenge, the staff of Fasintsara Health Center mentions, because support for the program has not yet been implemented here. When faced with cases of malnutrition, health workers can only advise patients’ caregivers on good feeding practices, even when they know that the child needs more in-depth care, or even hospitalization. Parents listen to the advice, but it is difficult for them to follow, since in the majority of cases they have limited means to access the types of foods recommended for balanced nutrition. Even to pay 2,000 Ariary (about $0.50 USD) for drugs or therapeutic foods, many cannot afford it and ask to pay in installments. The start of UHC here will be a great breath of fresh air for these vulnerable families seeking care.

Currently, if there is a complication that requires greater care than this basic health center can provide, the nearest city is Ambositra, 58 kilometers from Fasintsara, requiring a trip that takes a minimum of a day and a half on foot or 6-10 hours on motorbike (even more, depending on the season and the state of the road).

This situation is difficult – Dieu Donné says he sees complicated cases almost every day. One of the stories he told me made my blood run cold. In 2017, a young girl came to the health center to give birth and, there alone, Dieu Donné realized that the woman could not give birth vaginally and needed a C-section. But the nearest facility in the district that can perform this procedure is Ifanadiana District Hospital (about 120 kilometers away) or in Ambositra (outside of the district). Unfortunately, it was too late to take her there because she was already in labor. So Dieu Donné made the heavy decision to perform a craniotomy on the infant in an attempt to save the mother’s life. She survived but, sadly, her baby did not. According to Dieu Donné, this is far from an isolated case. It is typical that pregnant women arrive to the health center too late to be transferred to higher levels of care, and the outcome is sad; the staff too often must make a critical choice in order to avoid losing 2 lives.

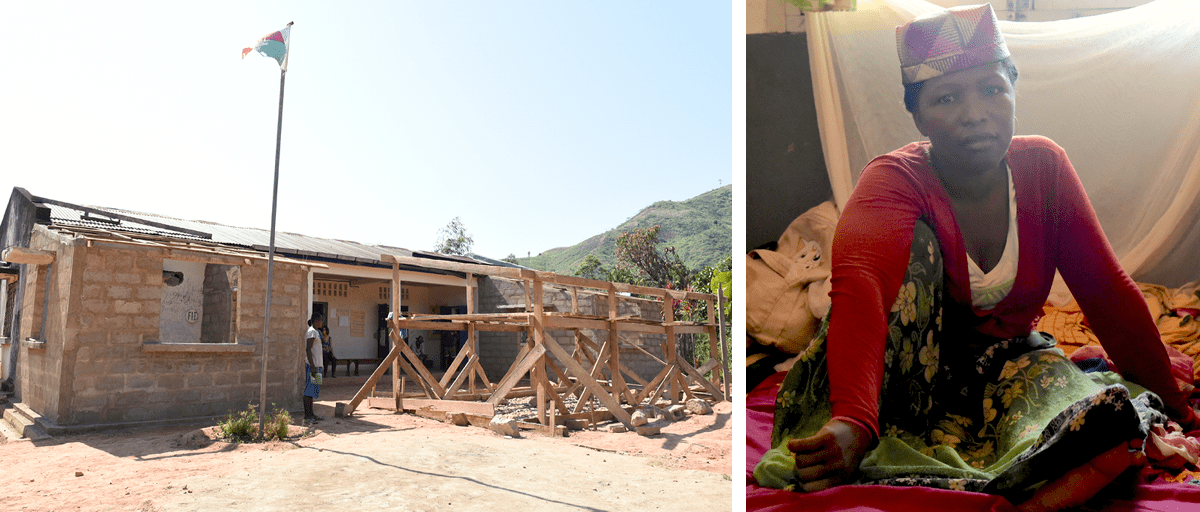

The day after our visit to Fasintsara, we continued on to Maroharatra, a town 12 kilometers from Fasintsara, or about 90 minutes by motorbike. Though renovations are underway, a primary challenge here at Maroharatra Health Center (above, left) is that utilization and service delivery are stagnating due to difficulties with the local supply chain.

As we tour around the health center and the renovations it has underway, we meet Aurélie (above, right), a 33-year-old woman from the village of Ampasimadinika, about 7 kilometers from the center. Her left leg has been badly swollen for about a month and a half, which made her journey to the health center even more difficult. She is lying on a mat on the floor with her mother Rasoamananjara, who stays by her bedside. There is only one functional bed in the facility, and it is occupied by an 18-year-old woman who has come to give birth to her first child. Due to lack of space in the health center, hospitalized people and newborn babies are in the same room.

Aurélie explains to us that she has been at the health center for a week and that her case requires a higher level support. To get the care that she needs, she must go to Ambohimanga du Sud Health Center, a health center that has been supported by PIVOT for over a year, where she can receive an analysis on her foot. However, due to lack of funds, she cannot pay the members of her community who have to take her there. Indeed, it is not uncommon to see almost all of the men in a village traveling to bring one single patient to a health center. This is a common part of Malagasy culture that shows the solidarity of the community. In these situations, the “cost” of transport is food for everyone on the trip, so if a patient’s family cannot afford to feed the villagers, the patient cannot travel.

For now, Aurélie’s only option is to remain at Maroharatra Health Center for however much time it takes for her husband (who remained home in the village) to collect enough money to provide food for the group who will take Auriele to Ambohimanga du Sud. But she has asked Aina, a midwife and Chief of Maroharatra Health Center, to do everything possible to cure her here, as she might not ever be able to get to another health center.

The next day, after our visit to Maroharatra, we decided to visit the Ambodimanga Nord Health Center (above, left) as a detour from our route back to Ambohimanga du Sud. This facility is classified as a “Level 1” health center, meaning that the services offered are more limited than the other “Level 2” health centers we have visited so far. When we arrive, we are so shocked to see the state of the spaces that serve as the delivery and hospitalization rooms (above, right), that we wonder how any human being, just like us, can be expected to give life or trust being taken care of in this place. Ranjato, PIVOT’s Head of Infrastructure, explains to us that almost all the remote health centers – and, above all, the Level 1 facilities – are in this state, not only in Ifanadiana District but all over Madagascar.

During our discussion with Lanto (left), the volunteer nurse of this health center, two people arrive: Celestine, an elderly lady, and her grandson Fabrice, age 15, who is ill. Lanto received them and, after assessing his symptoms and posing a few basic questions about the reason for their coming to the health center on this day, she gave Fabrice a rapid diagnostic test for malaria, which came back positive. The nurse proceeded to give them medicines that cost them 1000 Ariary (or about $0.25 USD) – one of the many costs that PIVOT covers for all patients who receive care in the 7 health structures we already support, but for this facility that service won’t begin until 2022.

On the last day of our trip, I realize that – even after working for PIVOT for over two years – this visit to this part of the district opened my eyes to the challenges of my compatriots: millions of men, women, and children in Madagascar who live in these remote areas, still with minimal access to basic health care. Having access to dignified care in a sanitary structure worthy of that name remains difficult, if not impossible, for too many.

The hope I hold on to is that in the next couple of years, as PIVOT expands to these remote corners of Ifanadiana District, anyone I have encountered on this expedition will be able to consider quality health care as a given. Support for healthcare leaders like Dieu Donné and nurses like Lanto is on the way, and I can’t wait to come back here in 2022 to see the difference it has made for thousands of patients just like Aurélie and Fabrice.